Abstract: The contemporary economy has witnessed a significant development of international trades, which might lead to the increase in disputes and the demand for resolving them. International Arbitration is a desirable method to resolve cross-border disputes in commerce. In practice, the parties engage in the international trade likely intend to to opt for dispute resolution through arbitration in Singapore, a country with the most developed arbitration system in Asia.

Thereby, the demand for recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral award in Vietnam has been increasing exponentially every year. This Article shall discuss the International Arbitration in Singapore involving Vietnamese parties and recognition and enforcement of such Arbitral Award under Vietnam legislation. An overview of Singapore arbitration system and Vietnam regulation upon the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards.

Overview of Singaporean Arbitration

The international arbitration conducted within the Singapore’s jurisdiction shall be governed by the Singapore International Arbitration Act of 1994 (“IAA 1994”), which closely adhere to the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration of 1985. The legal framework for commercial arbitration in Singapore is characterized by several fundamental aspects:

Firstly, regarding the jurisdiction of the arbitration, any dispute arising from commercial activities can be resolved through arbitration if agreed upon by the parties, except where such agreement to arbitrate is deemed contrary to public policy.

Secondly, regarding the arbitration agreement, the arbitration agreement is required to be in writing. Specifically, “An arbitration agreement is in writing if its content is recorded in any form, whether or not the arbitration agreement or contract has been concluded orally, by conduct, or in any other manner.”

Thirdly, regarding the number of arbitrators of the arbitral tribunal, IAA 1994 stipulates that it is determined by mutual agreement of the parties. In cases where the parties cannot reach an agreement, under Singapore law, the arbitral tribunal shall consist of a sole arbitrator, contradict to Vietnamese laws when the arbitral tribunal shall consist of three arbitrators. Another notable point in IAA 1994 is the provision for emergency arbitrators. In practice, there are situations where a party needs to apply for interim relief urgently and cannot wait for the arbitral tribunal decision or the establishment of the arbitral tribunal (which may take 1 or 2 months, or even longer). Therefore, Section 2.a of IAA 1994 has been amended to include provisions for Emergency Arbitrators within the concept of the “Arbitration Tribunal”. This amendment aims to provide Emergency Arbitrators with a legal status and authority similar to any other Arbitrator within a regular Arbitral Tribunal, ensuring that decisions made by Emergency Arbitrators are enforceable like those issued by other Arbitral Tribunal.

Finally, regarding the annulment of arbitral awards under Singaporean law, there are two significant points to note. Firstly, Singaporean law allows for the annulment of an award if a court finds that the arbitrator’s decision contradicts Singaporean public policy. This provision is in alignment with UNCITRAL’s model law and tends to be less controversial. In contrast, Vietnamese arbitration law allows for annulment if the award conflicts with fundamental principles of Vietnamese law. This provision has sparked considerable debate and inconsistencies in enforcement, potentially resulting in arbitrary annulment of arbitral awards.

Noteworthy experience for the Vietnamese party when engaging in the international arbitration proceeding in Singapore

Besides the fundamental legal framework governing international commercial arbitration under the Singapore International Arbitration Act of 1994, parties engaging in arbitration proceedings in Singapore must also consider the rules of the arbitration centres. In general, compare with the arbitral proceeding in Vietnam, the international arbitral procedure in Singapore may be more complex and rigid. During our experience while supporting parties involving in the international arbitration in Singapore, especially the Vietnamese parties, we acknowledge some notable points on the proceeding for the Vietnamese parties.

Commencement of Arbitral Proceeding

Pursuant to SIAC Rules, the arbitral proceedings shall commence by filing a Notice of Arbitration with the Registrar and the Respondent. Such process plays an indispensable role in starting the arbitral process as the date of commencement of the arbitral proceedings, accordingly, shall be the date of receipt of the complete Notice of Arbitration by the Registrar. This stage is significantly different from the arbitral proceeding in Vietnam when the arbitral proceeding shall be commence by the Statement of Claim.

In general, a Statement of Claim provides a comprehensive account of the facts supporting a claimant’s case, the legal basis for the claim, the relief sought, and quantifiable claims. It also requires material supporting documents to be attached. Conversely, a Notice of Arbitration may simply outline the nature and circumstances of the dispute, specify the relief sought, and provide an initial estimate of the claim amount.

While submitting both the Statement of Claim and Notice of Arbitration concurrently is allowed, the Claimant must ensure they have sufficient information and documentation beforehand. Otherwise, they may be constrained to the contents of the Statement and could incur additional costs if they need to amend it to include more facts, details, or claims.

Therefore, commencing arbitration proceedings with a Notice of Arbitration allows parties additional time to adequately prepare the Statement of Claim and address procedural matters beforehand, such as challenge the jurisdiction of arbitration, constitution of the arbitral tribunal, issuing the Procedural Order No. 1,…

Style of Submission

In the international arbitration in Singapore, a tribunal frequently establishes the fundamental procedural rules and timetable for arbitration at the outset through a procedural order, commonly known as Procedural Order No. 1. This order typically addresses various aspects including written communications, rules of evidence, the structure and style of written submissions, the contents of witness statements and expert reports, organizational details for the final hearing, and the overall procedural schedule.

One of the crucial but relatively unfamiliar aspects for Vietnamese parties participating in international arbitration in Singapore is determining the style of submission. Usually, there are two common styles of submission which are memorials and pleadings. The key distinction between the two lies in when witness statements and expert reports are presented. The underlying issue in the debate between memorials and pleadings revolves around whether parties should submit witness statements and/or expert reports concurrently with the pleadings and supporting evidence. Memorials closely resemble procedures in civil law jurisdictions such as Vietnam, whereas pleadings are more in line with practices in common law jurisdictions such as Singapore.

In order for a party to apply which style of submission, there are key considerations as follows:

- Whether the dispute hinges primarily on factual or legal issues. If factual matters dominate, opting for a memorial approach allows thorough examination and testing of each party’s case at every stage.

- Whether the issues in dispute are narrowly defined or span a broader spectrum. For disputes covering multiple issues, a pleadings approach helps clarify issues early, potentially saving resources on evidence preparation for moot points.

- Imbalances in the parties’ positions, such as significant financial or informational disparities. Parties with greater resources might prefer a memorial approach to increase upfront costs for the other party. Conversely, a pleading approach may benefit parties lacking full access to facts and documents, allowing them to present evidence after completing document production.

- The parties’ preference for efficiency and potential settlement prospects. Front-loading costs in advancing a case can highlight its strengths and weaknesses early, possibly encouraging settlement. A memorial approach typically accommodates a more condensed timetable.

Witnesses

In most international arbitration proceedings, witness testimony plays a crucial role. It complements documentary evidence and is essential for the arbitral tribunal to render decisions on factual or technical aspects of the case. Specifically, there may be two types of witnesses: witnesses of facts and expert witnesses.

Witnesses of facts, as their name suggests, typically offer evidence concerning objective facts pertinent to the dispute. They may testify about facts that cannot be established through documents alone or provide additional context that documents do not cover. Generally, fact witnesses are restricted from including personal opinions in their statements.

Expert witnesses typically testify within their own field of expertise, which often exceeds the tribunal’s specialized knowledge. They are commonly employed for tasks like quantifying damages, though their testimony can cover any area requiring specialized professional or technical knowledge beyond the tribunal’s expertise. This may include interpreting national laws, addressing engineering or scientific matters, assessing asset valuations, and more. Unlike fact witnesses, experts are generally permitted to include their professional opinions in their reports.

During the arbitration proceedings, when the parties request the presentation of a witness, there shall be direct examination and cross examination. Direct examination means that when a party request for the presentation of a witness, that party shall question the witness in front of the Tribunal to exploit details to illumine the unclear points of the case or to support that party’s argument. Cross examination means the counter party questions the witness for contrary purposes, they also may try to convince the Tribunal that the witness does not provide the truth, or to exploit the witness testimony for support their argument from another different point of view.

Appearing as a witness, giving evidence and being cross-examined is a daunting prospect, especially when this process is not very common in Vietnam. A witness will seek to rely on their legal counsel to assist them in preparing for this process.

On behalf of witnesses, they should be familiar with their own statement; study the relevant documents, especially those referred to in their own statement; know exactly the key aspects of the case. The main role of the Vietnamese counsel is working with the Vietnamese witness, meet or interact with Witnesses and Experts in order to discuss and prepare their prospective testimony.

In conducting the witness preparation, especially when there are different approaches to witness preparation across jurisdictions, the Vietnamese counsel should be conscious of a Vietnamese witness’s level of familiarity with the process of giving evidence of the international arbitration and assist witnesses to be familiar and comfortable with the process by explaining the nature and process of giving evidence. Besides, ensure that the witness understand their role in the arbitration proceedings.

Counsel may meet and confer with witnesses to ensure they are well equipped to provide evidence that assists the tribunal to determine the relevant factual issues and ultimately to resolve the parties’ dispute. In the process of obtaining the witness’s genuine recollection, it is proper for counsel to discuss with a witness documents as well as the other side’s case.

To prepare thoroughly for the cross-examination process, parties should focus on the following key issues:

- Listen attentively to each question and take a moment to consider your response, regardless of which party poses the question.

- Refrain from providing lengthy narrative answers. Focus directly on answering the questions posed and seek clarification if any question is unclear or ambiguous.

- Always testify truthfully about events or facts. It’s crucial for witnesses to distinguish between factual accounts and personal opinions. Their role is to present facts, not opinions.

- Communicate using clear and simple language, avoiding technical jargon or specialized terms related to specific professions. This approach helps ensure clarity and prevents misunderstandings, particularly when dealing with complex technical details in international arbitration where tribunal members may not possess detailed knowledge of every aspect.

- Avoid humor, slang, or irony during both direct and cross-examination. Maintaining a professional demeanor throughout the proceedings is essential.

- Lastly, particularly during cross-examination, witnesses have the right to request access to documents referred to by the opposing party. It is advisable for witnesses to ask the opposing party to present their evidence first if questions are based on specific statements.

Key features of international arbitration in Singapore

Court review of jurisdictional rulings

If the Tribunal decides, either as a preliminary matter or at any stage of the arbitration proceedings, that it has jurisdiction over the dispute, or conversely, that it lacks jurisdiction, any party has the right to appeal this ruling to the Singapore Courts. During the stages of setting aside and/or enforcement, the Singapore Courts may review the Tribunal’s decision regarding jurisdiction. Meanwhile, the Tribunal has the authority to proceed with the arbitration proceedings while awaiting the Singapore Courts’ final determination on the matter.

Court review of arbitral awards

When the place of arbitration is Singapore, a party may challenge the award by making an application to the Singapore High Court to set aside the award. The application must be made within three months of the date that the award is received by the applying party.

The Singapore court may set aside the award of arbitral tribunal if:

- a party to the arbitration agreement was under some incapacity;

- the arbitration agreement was not valid;

- the party making the application was not given proper notice of the appointment of an arbitrator or of the proceedings and was unable to present its case;

- the award dealt with a dispute not falling within the terms of the arbitration agreement;

- the tribunal was improperly constituted;

- the subject matter of the arbitration was not capable of settlement by arbitration;

- the award was contrary to public policy;

- the making of the award induced or affected by fraud or corruption;

- a breach of natural justice occurred in connection with the making of the award, by which the rights of a party were prejudiced.

Court ordered interim relief in aid of arbitration

It can be seen that this is a distinctive feature allowing Singapore Courts the power to grant interim relief in aid of both Singapore seated and foreign seated arbitration, including:

- Allowing evidence to be presented by affidavit.

- Preserving, interim custody, or arranging for the sale of property that is the subject of the dispute.

- Preserving and interim custody of evidence.

- Securing the amount in dispute.

- Preventing the dissipation of assets to ensure any potential award remains enforceable.

- Issuing interim injunctions or any other necessary interim measures.

- Enforcing obligations related to confidentiality.

Third-party litigation funding

There exists a notable contrast between the regulations governing third-party litigation funding (TPF) in Vietnam and Singapore. TPF involves an agreement where an entity outside the dispute provides financial support to a party to cover the costs of proceedings in exchange for compensation.

Under Singaporean law, TPF is permissible for international arbitration. Consequently, if arbitration is seated in Singapore:

- Parties face no obstacles in obtaining TPF.

- TPF is not a grounds for setting aside arbitral awards in Singapore.

In contrast, Vietnamese regulations do not explicitly address TPF, and it is not a prevalent practice within the country. This disparity underscores the differing legal landscapes between Vietnam and Singapore concerning the use of third-party funding in arbitration.

Recognition and Enforcement of Singaporean arbitral awards in Vietnam

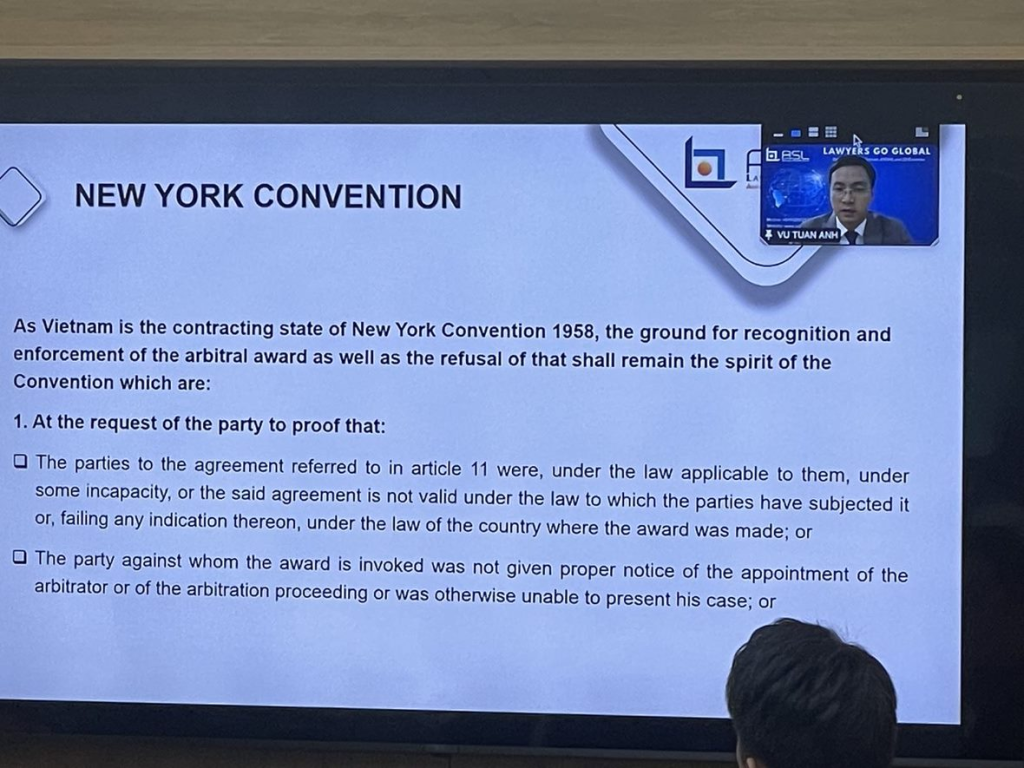

As with legal customs in other countries, an international arbitral award needs to be recognised by an competent Vietnamese Court before enforcement in Vietnam. Currently, the Vietnamese laws and regulations do not set the specific legal grounds for the recognition but, otherwise, set grounds for the non-recognition. According to Article 459 of the 2015 Code of Civil procedure based on the same spirit as Article V of New York Convention 1958, cases of non-recognition include:

- The parties of the arbitration agreement do not have capacity to conclude such agreement according to law applicable;

- The arbitration agreement is not legally effective according to the law chosen to be applied or the law of where the award is made;

- The judgement debtors are not promptly and conformably notified of the appointment of arbitrator officer and of procedures for processing the disputes at foreign arbitrator, or due to other plausible reasons, they cannot exercise their procedure rights;

- The foreign arbitrator’s award over a dispute is not requested to be settled by any parties or exceeds the request of the arbitration agreement;

- Compositions of foreign arbitrator and/or procedures for settlement of disputes conducted by foreign arbitrator are not conformable to the arbitration agreement or to the law where the foreign arbitrator’s award has been made, in case the arbitration agreement does not provide for such matters;

- The foreign arbitrator’s award has not had compulsory legal effect on parties;

- The enforcement of the foreign arbitrator’s award has been canceled or terminated by a competent agency of the country where such award is made or the law that is applied;

- According to Vietnam’s law, the dispute shall not be settled according to arbitral procedures;

- The recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitrator’s awards are contrary to basic principles of law of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

On the basis that Singapore and Vietnam are the contracting states of the New York Convention 1958, in case the arbitral award does not fall into the abovementioned cases, such arbitral award shall be recognized and enforced in Vietnam if the judgment debtors being individuals reside or work in Vietnam, or the judgment debtors being agencies or organizations are headquartered in Vietnam or their properties related to the enforcement of the judgments or decisions of foreign Courts or foreign arbitral award exist in Vietnam at the time when the applications are filed.

In general, based on the pulic data of the Vietnam Ministry of Justice on the status of recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral award in Vietnam from 2012 to 2019, we acknowledge that the non-recognized foreign arbitral award accounts for 34% of the foreign arbitral award applied for recognition and enforcement in Vietnam.

The main reasons leading to the refusal to recognize arbitral awards are incorrect arbitration agreements, jurisdictional issues, procedural irregularities, especially improper notification procedures not in accordance with applicable arbitration procedural rules, contrary to Vietnamese legal principles,… Some considerable actual cases that are worth mentioning include:

(i) Decision No. 01/2017/KDTM-ST dated 27/11/2013 of the People’s Court of Thai Binh province on non-recognition of the Arbitration Award of the Arbitrator of the ICA. In this case, the parties signing the arbitration agreement do not have the capacity to sign the agreement, the contract only has the signatures of both parties without the name and position of the signer. Therefore, the arbitration agreement in this case has no binding legal value, according to Art. 459.1.a of the 2015 Civil Procedure Code.

(ii) Decision No. 01/2016/QDKDTM-ST dated 30/5/2016 of the People’s Court of Nam Dinh province on not recognising the Arbitration Award of the ICA Arbitration Council. In this case, based on the dispute records of the two contracting parties, one contracting party was not promptly and conformably notified of the appointment of an arbitral officer and of procedures for processing the disputes at foreign arbitrator. Besides, one party unilaterally sued the other party to arbitration and imposed an arbitration settlement, which is against the basic principles of Vietnamese law. Therefore, this case falls under the case of not recognised according to the provisions of Art. 459.1.c and Art. 459.2.b of the 2015 Civil Procedure Code.

(iii) Decision No. 188/2021/QD-PT dated 31/3/2021 of the High People’s Court in Hanoi did not recognise award No. 5171 (2016) S.Z.A.ZI of the Guangzhou Arbitration Commission of China due to violation of arbitration proceedings. The reason for non-recognition stems from the fact that the arbitration council in this case did not consider the debtor’s counterclaim, violating Article 19 of the Arbitration Rules of the Guangzhou Arbitration Commission and falls under the case of not being recognised according to the provisions of Art. 459.1.d of the 2015 Civil Procedure Code.

This rate indicates that the recognition of arbitral awards in Vietnam still faces many limitations and raises doubts about the effectiveness of international arbitration proceedings. However, it cannot be denied that this rate has significantly decreased in recent years as parties have become more familiar with international arbitration procedures and the requirements of Vietnamese law regarding the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards in Vietnam.

In the era of rapid international trade development, particularly with investors from Asian countries, accessing the international arbitration system is seen as essential for Vietnamese parties. Moreover, to ensure that international arbitration proceedings are conducted efficiently, maximizing legal and economic benefits, collaboration between businesses and experienced law firms in arbitration is crucial.

ASL Law is a leading full-service and independent Vietnamese law firm made up of experienced and talented lawyers. ASL Law is ranked as the top tier Law Firm in Vietnam by Legal500, Asia Law, WTR, and Asia Business Law Journal. Based in both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, the firm’s main purpose is to provide the most practical, efficient and lawful advice to its domestic and international clients. If we can be of assistance, please email to [email protected].

ASL LAW is the top-tier Vietnam law firm for litigation and dispute resolution. If you need any advice, please contact us for further information or collaboration.

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt 中文 (中国)

中文 (中国) 日本語

日本語